The Alhambra in Granada, Spain, is one of the most complete surviving examples of Islamic architecture in Europe. During a recent visit, I studied the construction and decorative features of this palace complex to gain insight into the intentionality behind each element. As President of The Green Mission Inc. and Probity Appraisal Group, my work centers on valuing architectural elements that are deconstructed for reuse in the United States. This perspective prompts a different kind of architectural inquiry. Rather than viewing buildings as monolithic works, we evaluate them as layered compositions of salvageable materials, often with roots in global traditions. Nowhere is this contrast more evident than in comparing the unified design vocabulary of the Alhambra with the architectural fragments recovered from buildings across New York and other American cities. Many of these salvaged pieces reflect direct stylistic borrowing from the Moorish world. When considered side by side, the connections become clear and surprisingly instructive.

The Alhambra: Unified Craftsmanship

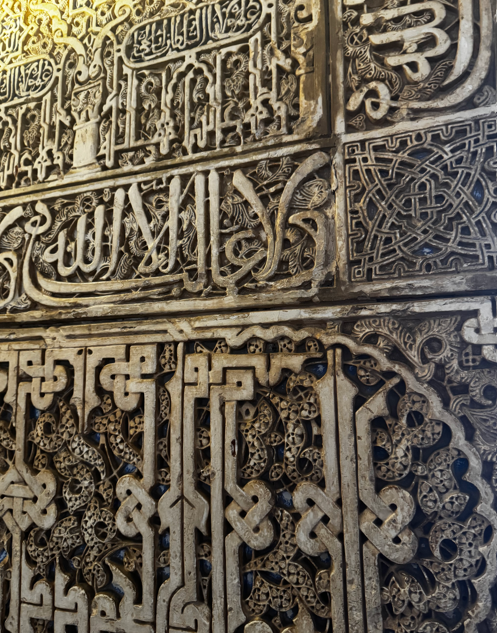

The Alhambra, built primarily during the 13th and 14th centuries by the Nasrid dynasty, presents a vision of architecture in which structure and ornament are fully integrated. Courtyards such as the Court of the Lions serve as both spatial centers and compositional frameworks. Slender columns support arcaded porticoes, and every surface is treated as a canvas for geometric tilework, carved stucco, or inscribed calligraphy. Above, muqarnas vaults and coffered wood ceilings modulate light and shadow. These elements were not applied as afterthoughts but designed as a cohesive whole, often using earth, plaster, tile, and wood sourced locally. The architecture was meant to evoke a vision of paradise, constructed with humble materials elevated by meticulous craftsmanship.

Despite being built with perishable materials, the Alhambra has endured for centuries. Its continued preservation is due in part to its structural simplicity and its layered detailing, which allows sections to be repaired or replaced while preserving aesthetic integrity. This modular quality is worth noting because it echoes, although unintentionally, a principle that underlies contemporary deconstruction in the United States: buildings are composed of individual components that can be disassembled, valued, and repurposed.

Salvaged Moorish Elements in the American Built Environment

In American cities, especially in New York, elements inspired by the Alhambra and broader Moorish design traditions were often inserted as stylistic flourishes in otherwise unrelated structures. These pieces, once part of early 20th-century buildings, are now frequently encountered during deconstruction projects managed by our firm. In our appraisals, we identify and assign IRS defined Fair Market Value to architectural elements like horseshoe arches, muqarnas-inspired plaster brackets, polychrome tile panels, hand-painted Moorish beams, and pierced wood screens. These are not relics of Islamic Spain, but they are deliberate nods to that tradition.

Buildings constructed during America’s Gilded Age and through the 1920s regularly incorporated Moorish Revival features. Theaters, synagogues, lodges, and hotels included domed ceilings, patterned tilework, and carved stone screens clearly referencing the Alhambra. One example is the Mecca Temple (now New York City Center), completed in 1923. The exterior includes polychrome glazed terra cotta, bulbous domes, and horseshoe arches. Inside, ceiling ornament recalls muqarnas vaults, and the surface decoration follows the same rhythmic layering of geometry seen in Granada.

Other examples include the Central Synagogue (1872), the Eldridge Street Synagogue (1887), and the Village East Theater (1926), which exhibit arched openings, painted ceilings, and stained-glass windows arranged in interlacing Islamic motifs. These buildings often borrowed specific patterns from the Alhambra and adapted them to modern functions. Many of these properties have since been demolished or converted, and their ornamental elements, like mantels, ceilings, panels, plaster fragments, have entered the salvage market.

• City Center 55th Theater (formerly Mecca Temple)

Deconstruction and the Preservation of Architectural Style

The deconstruction process in the United States differs from demolition in that it aims to extract usable materials for resale, reuse, or donation. Through our work at The Green Mission Inc., we regularly encounter architectural elements rooted in Moorish design, sometimes removed from buildings less than 100 years old. While the Alhambra endures as a whole, these American references often survive only in pieces. Their removal from walls, ceilings, and façades allows us to analyze and preserve them independently of the structures that once held them.

This fragmented survival mirrors the eclectic nature of early 20th-century American architecture. Unlike the cohesive composition of the Alhambra, buildings in New York from the same era were often built in revivalist styles. Gothic, Beaux-Arts, Egyptian, and Moorish influences were layered onto steel-framed structures. Architects and developers freely borrowed motifs, treating architectural history as a catalog of ornament. This produced buildings that could be stylistically rich but also modular in the sense that the ornament was often surface-applied and detachable.

Because of this modularity, salvaged components from Moorish Revival buildings in the U.S. retain integrity even after their host buildings are gone. For appraisers, this means the value of these elements must be assessed not only on their materials and condition but also on their historical references and design lineage. A hand-painted tile panel or horseshoe arch surround may carry more value if it clearly imitates forms found in the Alhambra or reflects broader Andalusian traditions.

Comparing Contexts: Wholeness and Fragmentation

The Alhambra’s architecture reflects a cultural intention to create a world unto itself. Every column, arch, and decorative motif was designed in service of that vision. By contrast, many American buildings from the early 20th century were built as pastiches of earlier styles. They pulled in motifs for dramatic or theatrical effect, often without concern for cultural continuity. The result is that while the Alhambra offers a unified architectural language, New York’s revival buildings were more like visual experiments in translation.

Yet it is precisely this difference that makes the salvage market in the U.S. so rich. Because ornamentation was often surface-mounted or structurally independent, it can be recovered, cataloged, and reused. That process not only gives new life to historic materials but also allows contemporary designers to re-engage with older styles, including those rooted in Islamic architecture.

In our appraisal work, we frequently cite stylistic origins to substantiate the historical and aesthetic value of salvaged elements. For example, a screen of carved wood latticework that once flanked an arched window in a demolished theater may reference Andalusian mashrabiya screens. Similarly, an embossed metal panel with interlaced patterns may be modeled after zellij tile arrangements from Granada. These stylistic connections increase the interpretive value of the object and help us justify market comparisons.

Studying the Alhambra firsthand and comparing it to salvaged architectural materials in the United States highlights a fundamental difference in how architecture is conceived and valued. The Alhambra represents architecture as holistic art, built to express a specific worldview. In contrast, many American buildings from the early 1900s used architectural language in fragments, creating opportunities for those fragments to outlive their original contexts.

In my role as President of The Green Mission Inc., I see this not as a shortcoming, but as a potential. Through deconstruction, these architectural fragments can be preserved, reappraised, and reintegrated into new projects. In this way, we continue the story, connecting the craftsmanship of the past with the sustainability needs of the present. The Alhambra may endure as a whole, but in our work, we ensure that even pieces of buildings can retain meaning and value.