President and CEO, The Green Mission Inc. and Probity Appraisal Group

Personal property appraisal is not an exact science. Unlike securities or commodities, there is no public exchange that definitively determines the value of a used Barbara Barry armchair, a dated Formica kitchen, or a reclaimed vanity. Instead, appraisers follow the IRS’s definition of Fair Market Value (FMV), which under Treasury Regulation §1.170A-1(c)(2) is:

“The price at which the property would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller, neither being under any compulsion to buy or to sell and both having reasonable knowledge of relevant facts.”

With this principle in mind, two appraisers evaluating the same item may justifiably land on different conclusions. One appraiser may rate a Barbara Barry piece as in Very Good condition and value it at $1,000. Another might assess it as Excellent and assign a $1,200 FMV. A third may consider it merely Good and arrive at $800. These differences are not mistakes, they are natural outcomes of an informed but interpretive process. Over time, responsible appraisers trend toward the median, balancing market data, experience, and condition assessment.

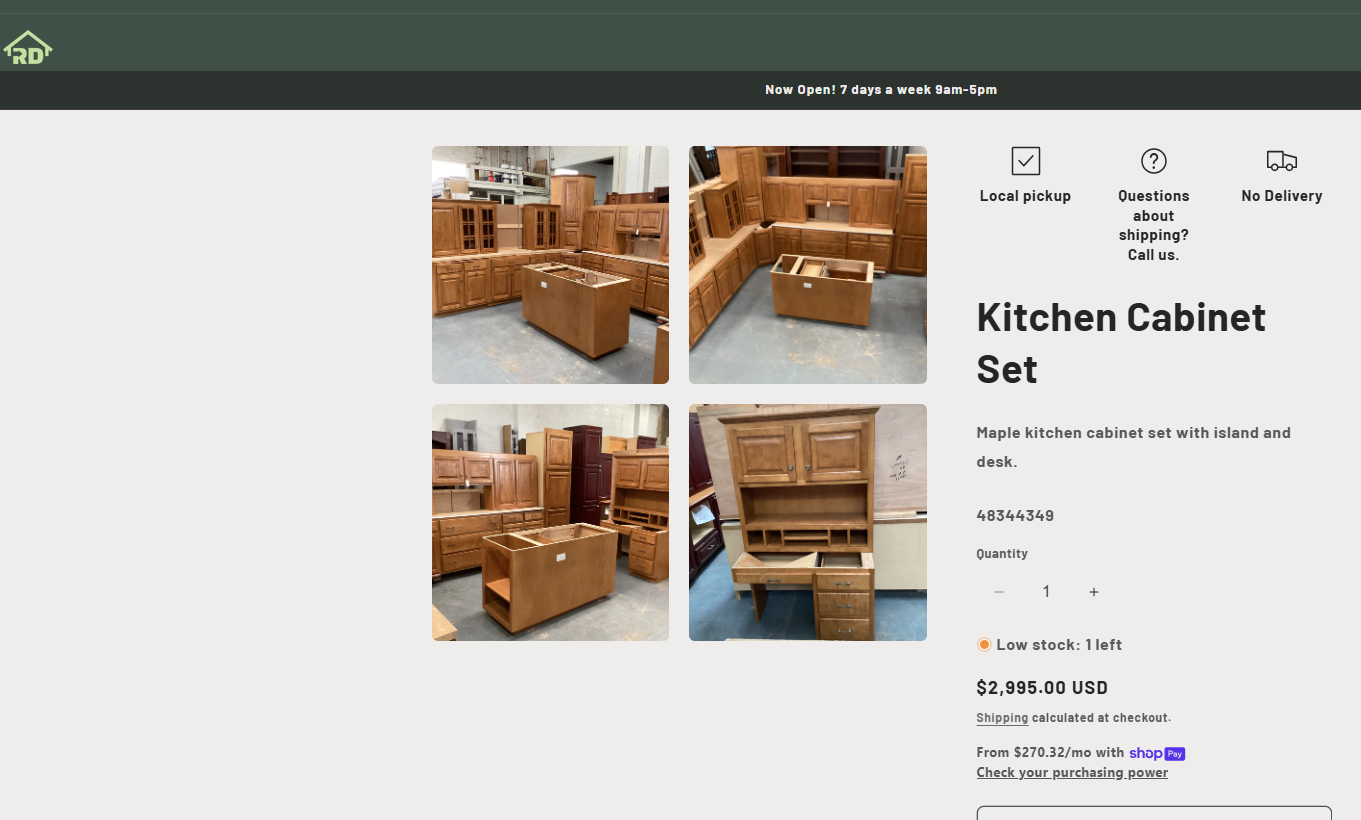

At The Green Mission Inc. and Probity Appraisal Group, we believe accuracy in valuations matters, not just ethically, but legally and financially. Recently, we were contacted by two potential donors who had also reached out to other appraisers. One was seeking to donate a dated kitchen set with Formica countertops and an older sink. After analyzing comparable sales and the resale feasibility of similar cabinetry (including rejection policies of nearby ReStores), we advised the client to take a deduction of $5,000 or less, there was no appraisal needed. (The IRS only requires appraisals for anything valued $5,000 or more.) The other appraiser quoted the FMV at $25,000.

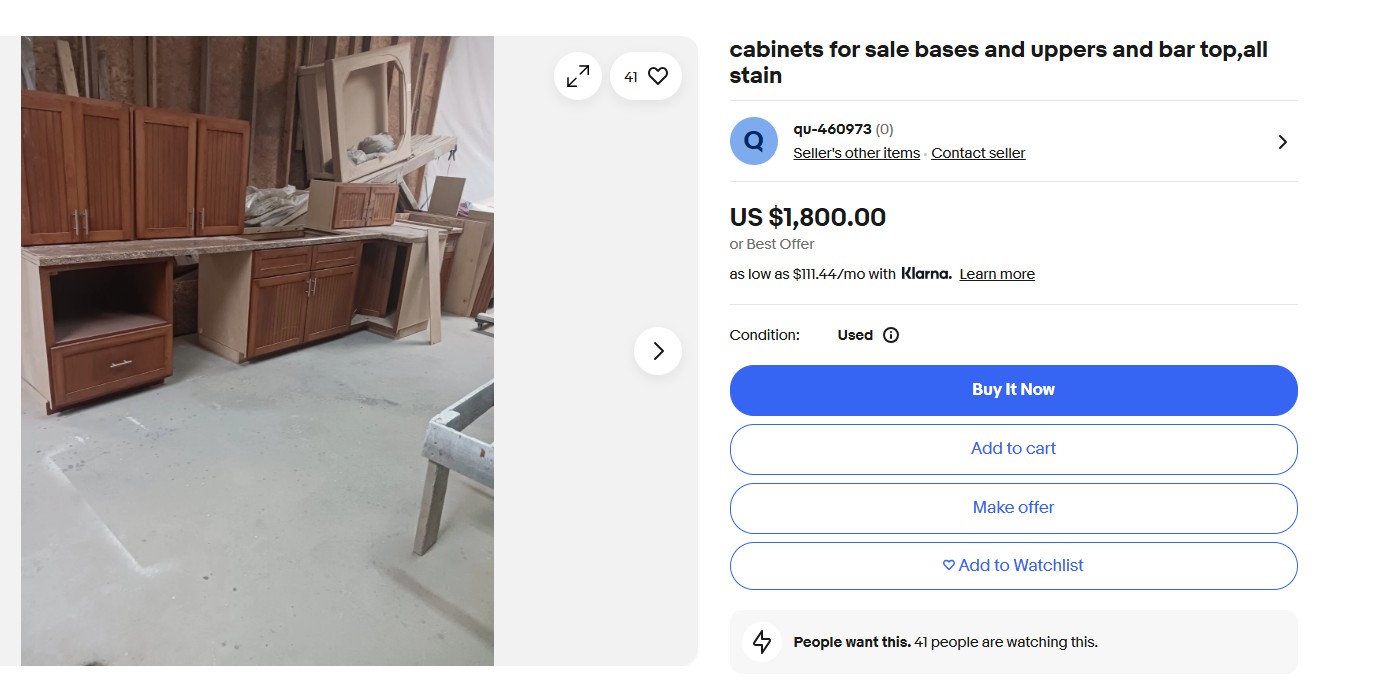

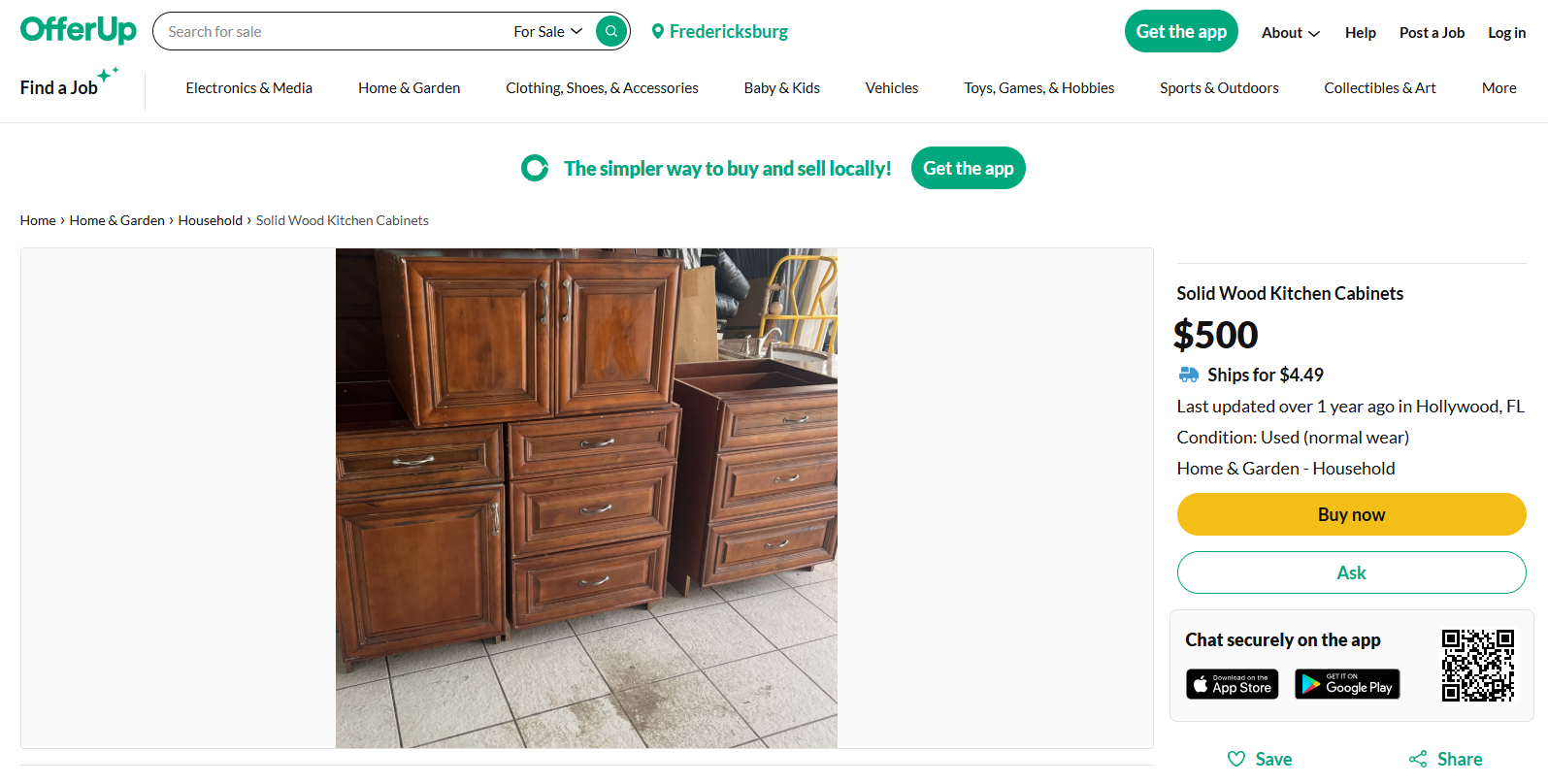

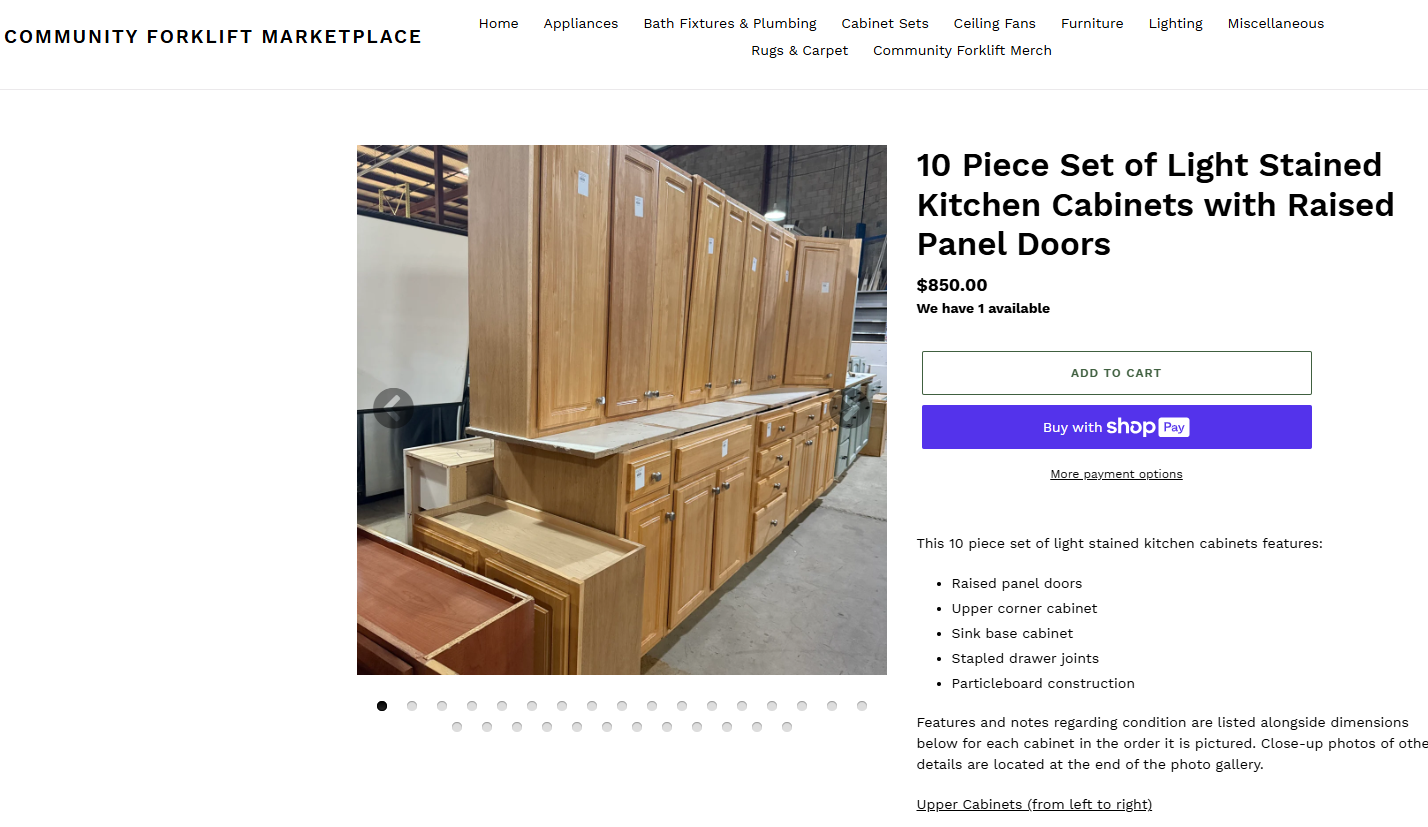

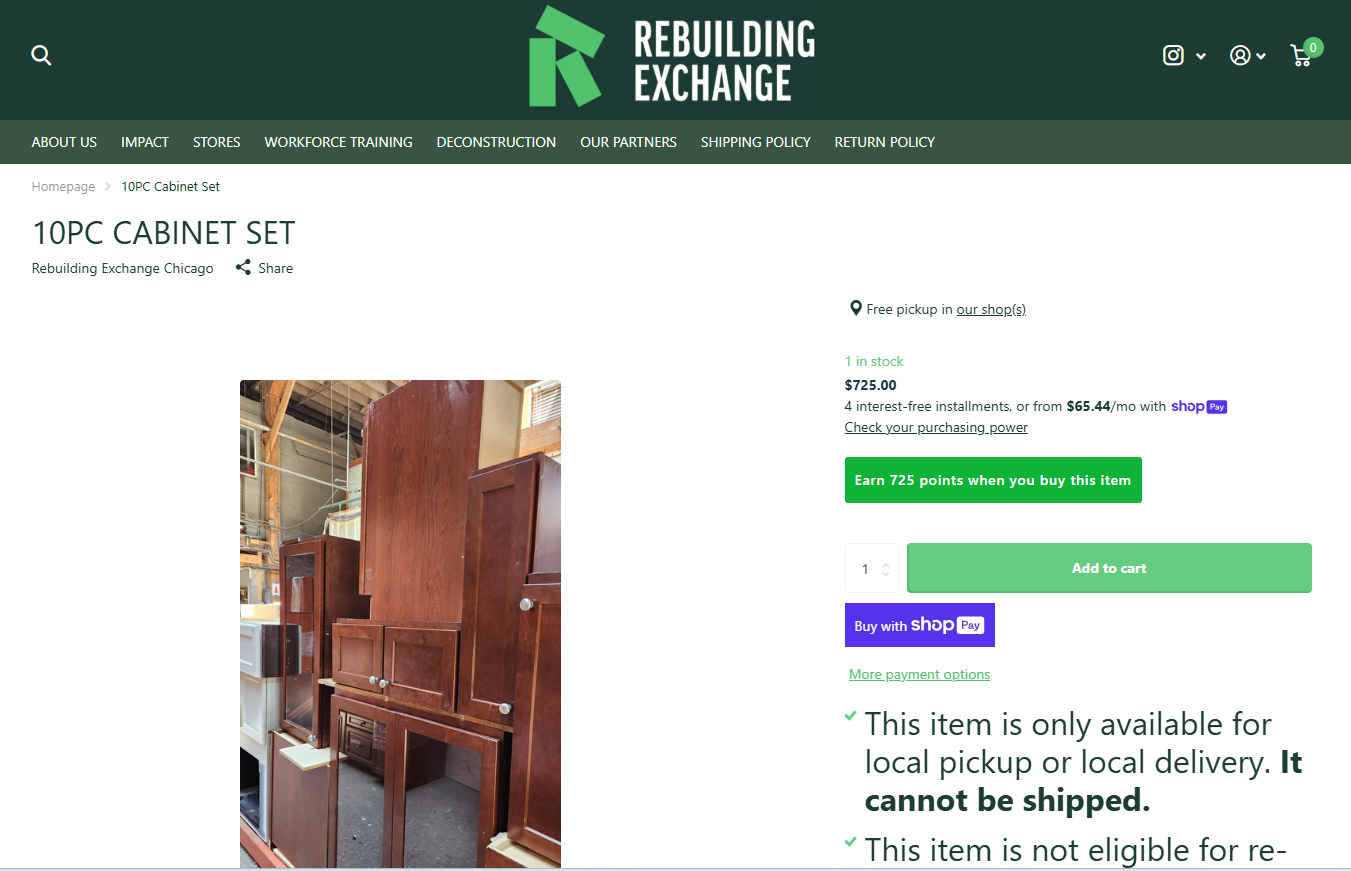

Here are a few readily available comparable sales of similar cabinetry. If we can find these within a few minutes, so can the IRS.

In another case, our team appraised a 1,500 square foot dated residential property donation far below a competing appraiser, who valued it $100,000 higher. One client thanked us for our transparency and submitted a modest deduction without an appraisal. The other urged us to raise our number to match the inflated appraisal. We declined. Unless there were hidden diamonds embedded in a bathroom vanity we missed during the site inspection, our value, grounded in methodology, market data, and ethical practice, was firm. That donor chose to "take their chances with the IRS."

This brings us to a critical point: the penalties for overstating charitable contributions are severe and fall entirely on the taxpayer, not the appraiser. Per IRC §6662(e) and (h), a taxpayer can be assessed a 20% penalty for a substantial valuation misstatement (if the value claimed is 150% or more of the correct amount), and a 40% penalty for a gross misstatement (200% or more of FMV). There is no federal licensure for personal property appraisers—unlike CPAs or CFPs. Taxpayers must be discerning. A high number may feel beneficial today, but it may not hold up under audit tomorrow.

This is a rare and complex deduction—one that supports sustainability, diverts usable materials from landfills, and encourages deconstruction over demolition. To preserve this important incentive, we must uphold high standards in our industry while also investing in the growth of the secondary market. The long-term goal is not simply to deduct used building materials, but to build an ecosystem where their resale is viable and commonplace.

In short: Responsible valuations are not just about numbers. They are about trust, compliance, and the future of reuse. Let us protect this deduction by doing it right.